February 20, 2023 at 8:58 pm | Updated February 20, 2023 at 8:58 pm | 12 min read

- Significant variations exist in the mango quality and yield from various regions worldwide.

- Integrating objective quality control and monitoring based on internal physiological parameters can help growers and suppliers maintain mango quality and their income in the supply chain.

- A systemic and coordinated approach is necessary to improve mango quality, as preharvest practices significantly impact harvest and postharvest quality. Regulatory and support associations can be crucial in the mango value chain.

Mango yield and quality are low even though the fruit has been cultivated for a long time. External and internal parameters, shelf life potential, and nutraceutical contents define fruit quality. These attributes show wide variations between and within trees, orchards, and regions from one year to the next. These quality variations reduce the market and export potential of crops. Optimizing quality and improving consistency can help increase profits. It will simultaneously reduce food loss and waste, making food production more sustainable. Read more to find out how mango quality can be improved.

What People Want in Mangoes

Mango is a popular tropical fruit, eaten for its taste but increasingly also for its nutrient content. Mango is the fruit with the highest vitamin A or carotene content, vitamin C, and minerals. The fruits also contain sugar, fiber, and proteins.

Since mangoes are very nutritional, they are used as food for babies and invalids.

Subscribe to the Felix instruments Weekly article series.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact

Therefore, it is crucial to optimize quality by looking at the various aspects that affect it, in the entire supply chain, from preharvest farm phases to harvest and postharvest stages.

Consumers’ interest in organic products has scientists innovating and finding ways to maximize yield and quality without using chemicals.

How people consume mango is also changing. People can now choose from fresh, frozen, entire, cut, and processed products. Most of the fruits are slated for fresh consumption. But the demand is also increasing for primary and secondary mango products, such as juice, confectionery, ice cream, and bakery.

Global Mango Production

Though mango can grow in many parts of the world, commercial production for pulp and juice is restricted to a few areas. However, due to consumers’ increased health consciousness and income, a 6.7% yearly growth rate is expected in demand for processed mango products between 2022 and 2028. As a result, the global processed mango products market will be worth USD 3,237.7 Million in 2028, up from USD 2,194.1 Million in 2021.

In 2021, India remained the largest mango producer, with a volume of 24.7M metric tons (MMT), but Indians consume most of it, and only 1% is exported. In 2022, India was still the most prominent producer contributing to 51% of global production. Most mango varieties from north India are used for the table, while mangoes from southern India are used to make pulp. However, one Indian state Uttar Pradesh provides 21% of global processed pulp. The main varieties processed are Alphonso and totapuri.

The best quality mangoes also come from India, namely the Alphonso, called the King of Mangoes, and is highly sought for taste globally.

Indonesia is the second largest producer, cultivating 3.6 MMT. Mexico and China are the third largest producers with 2.4 MMT and are essential exporters. The other major producers are Pakistan (2.3 MMT), Brazil (2.1 MMT), and Nigeria (0.8 MMT).

The largest exporter was Thailand selling mango worth USD 827M overseas. And China was the prominent importer, taking in USD 832M worth of mangoes.

Mango yields can vary from year to year. So, while India had lower sales in 2022, and Brazil is expected to have 19% lower sales year over year (YOY), Ecuador will see a rise of 3% and Mexico by 10%.

The predominant varieties produced differ depending on the region. In India, where 1000 mango varieties grow, the popular cultivars are Alphonso and totapuri. The leading Mexican types are

- 40% of Tommy Atkins,

- 27% of Ataulfo/Honey,

- 19% of Kent,

- 11% of Keith, and

- the rest accounts for only 3% of its trade.

While the USA imports mostly Keitt (63%) and Tommy Atkins (33%).

These vast amounts of fruits must be monitored closely to ensure that consumers get the fruit mature but not ripe. Since mango is a climacteric fruit, it will ripen after harvest, and suppliers seek to delay ripening by manipulating the storage conditions.

Quality Parameters and Monitoring Methods

Regardless of the variety, some practices are standard to ensure mango quality.

From the farm to when they reach retailers, mango quality is monitored to check for maturity and ripeness.

External color is not recommended as a quality parameter, as some varieties remain green even when ripe, like Keitt. Therefore, the traditional parameters were internal color and fruit shape (full shoulders). Later, people began to use refractometers for sugar or BRIX estimation and penetrometers for firmness. However, the four methods are destructive, tedious, and need time.

Nowadays, objective measurements of internal color, BRIX, acidity, and dry matter are made using non-destructive technology such as near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy.

The F-751 Mango Quality Meter manufactured by Felix Instruments Applied Food Science is an industry standard used in the mango supply chain and for research. The tool has integrated Chemometric analysis for the complex data collected to give results within 12 seconds.

Maturity can also be judged by using a combination of parameters. However, dry matter at harvest is gaining predominance as it is an excellent predictor of postharvest quality and consumer preferences.

The optimal average dry matter content at harvest is available for the most popular varieties to use as a harvest index. Harvesting at the correct time, when the fruits are mature, ensures that the mangoes meet consumers’ preferences and are accepted.

In the postharvest stages, producers and suppliers continue to use BRIX, acidity, and dry matter to monitor quality. They track damage and spoilage due to handling, the impact of weather, control pests and diseases, check storage and transport impact, processing needs, and meet government regulations in international trade. Regular checking and culling of spoilt fruits can save the rest of the crop.

Storage & Transport Conditions

Mangoes are susceptible to damage and pressure. Therefore, the fruits must be customized for packaging, handling, transport, and storage conditions.

Improper handling and packaging can bruise fruits and trigger infections by pathogens from the fruits or handlers.

Mangoes should be packed in a single layer in crates and cartons. The fruits are wrapped with a straw, wood wool, and bast buffer.

To ensure quality while transport and storage, care must be taken to ensure that the skin is undamaged. The maximum storage and transport time is 14-25 days.

The atmospheric conditions must also be controlled to optimize storage time. Warm storage conditions lower quality and yield by triggering ripening and senescence.

Controlled atmospheres are the best storage means, as they have conditions that control respiration, which hastens ripening. Therefore, the ideal conditions for storage and transport according to TIS are:

Temperature: The range is between 12.2 – 13.3°C. The loading temperature should be 12.2°C, while the recommended travel temperature varies between 10-14°C for various varieties.

Relative humidity: Though dependent on varieties, the average range is 85-90% and prevents weight loss due to moisture loss.

Carbon dioxide: 5% of the gas is ideal for preventing high respiration rates.

Oxygen level: 5% oxygen is necessary to ensure that the high CO2 content doesn’t result in the fermentation and spoilage of mangoes.

Ethylene scrubbing: 60-80 circulations per hour are needed to prevent ethylene accumulation since mangoes are very sensitive to the phytohormone. Ventilation also controls CO2; failure to do so can lead to fermentation due to high levels of CO2 and less O2 from respiration.

The three gases can be monitored and controlled by choosing a single tool. Felix Instruments offers a choice of several gas analysis devices from which the stakeholders can choose. One of them is the F-950 Three Gas Analyzer.

Since the storage time is short, transporting mangoes to temperate countries requires air flights. Before transport, the containers must be cleaned, sanitized, and precooled before the fruits are loaded. The cargo should be protected from precipitation as moisture can lead to premature spoilage from rotting and mold. If slower transport like a ship is used, the consignments must be checked for diseases.

Storage conditions of mangoes must extend the life of fruits and maintain their quality. Mangoes can suffer chilling injury in the 5-12 °C range, with the exact temperature depending on the variety. For example, chilling injury occurs in Tommy, Atkins, and Keitt at 10°C and Ataulfo and Kent at 12.2°C

Treating mangoes with ethylene at 20 – 22.2°C ripens the fruits for sale. Artificial ripening with ethylene increases consumer acceptance to 87% from 39% for untreated mangoes. Mangoes are ripened with ethylene exposure for 24 hours. These fruits take three to nine days to mature. Mangoes given the postharvest hot water treatment do not need ethylene and will ripen in 2-6 days when kept at 20 – 22.2°C.

In retail stores, mangoes shouldn’t be cold stored. Instead, mangoes must ideally be displayed at a room temperature of 21.1°C to prevent chilling injury.

Local Innovations

Small-scale producers targeting local markets use natural methods or local materials to improve mango shelf life and quality. For example, in Sudan, wooden frames are covered with jute and wetted twice daily to cool temperatures by 3°C and increase relative humidity compared to conventional conditions. As a result, the mango’s quality was maintained, and shelf life increased from four in control to nine days in jute rooms.

Or the pot-in-pot method, where a smaller pot is placed inside a large pot, and fruits are kept in the small pot and covered with a damp cloth. This method keeps mangoes without spoilage for 20 days, whereas control fruits kept under shade showed 80% spoilage in 15 days.

Best Practices

Best practices to optimize quality should consider all factors influencing mango quality and will depend on preharvest and postharvest conditions.

Preharvest

The amount of photosynthesis is correlated with the number of inflorescences and fruits, while biomass accumulation and water supply affect quality. So proper nutrient and water management are necessary to ensure flower set and fruit development.

- Ring cutting a month before the flower set can increase flower number by restricting the movement of photosynthates to the roots.

- Early fruit size affects fruit development. Fruits that start larger will have better quality at harvest but have a shorter shelf life. So farmers can regulate the supply of nutrients based on their target mango market.

- Differences among branches in a tree will also influence mango quality. The tree architecture is essential and can be achieved through pruning and shaping the tree after harvest to improve light penetration and air movement in the succeeding years.

- Controlling pests and diseases on the farm can eliminate their expected negative impact on the growth of fruits. The common problems are the longhorn beetle, armyworm, leafhopper, etc. Growers should also monitor and control everyday biotic stresses like powdery mildew, gummosis, anthracnose, etc.

Postharvest

Mangoes must be harvested when green but completely mature but unripe. Once harvested, producers can take several steps to increase their ROI by maintaining fruit quality.

- Preventing sap burn is essential to maintain quality. When the mango is harvested, the broken stem exudes sap, which sticks to the skin damaging it and promoting microbial infection. Moreover, the sap affects the appearance lowering quality and reducing prices for crops suffering from sap burn. Proper choice of harvest time, stalk retention, storage, packing, and treatments with heat or dipping in oil or a mixture of detergent and calcium hydroxide can eliminate this problem.

- Postharvest treatments like edible bio wax immediately after harvest can control diseases and preserve fruit quality parameters like firmness, BRIX, and acidity. Bio wax-treated mangoes showed 90-96% marketability compared to the 83% of untreated fruits that could be marketed.

- Postharvest pest control, such as submerging mangoes in hot water, is a standard treatment to control fruit fly numbers before export to regions like the USA, see Figure 1.

- Sort and group mangoes according to ripeness, size, and variety. Avoid stacking fruits too high, and do not display them in containers that could apply pressure.

Regulatory and Industry Support Organizations

Growers and suppliers can turn to regulatory and industry support organizations to determine the best practices they should follow and the requirements of specific importing countries.

Each country has its own national and commercial associations. For example, consider India, the largest mango producer.

APEDA, or the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority, is the national body regulating fresh and processed mango sales in India by providing protocols for mango exporters. This protocol specifies harvest time, procedure, postharvest treatment methods for pests and diseases, sorting, grading, fruit quality, etc.

In addition, there are national-level groups like the All India Mango Growers Association (AIMGA) or regional groups catering to the needs of farmers. There are also groups formed based on the mango variety produced. For example, the Konkan Alphonso Mango Producers and Sellers’ Association worked to get Geographical Indication (GI) tags for their growers in Konkan. The association protects their interests by restricting growers in other regions from using the Alphonso tag.

Maturity requirements

The regulatory bodies are beginning to use internal quality parameters to set standards for exported and imported mangoes. The practice occurs more at national levels than at international organizations.

For example, APEDA mandates that mangoes meant for export must have 7-8% Total soluble solids (TSS) or sugars and an acidity of 4.0 pH at harvest, etc.

Mangoes exported to the EU from anywhere worldwide should have sufficient maturity to continue ripening. The color and firmness of a batch must be uniform, even though it will vary depending on the variety. There can be additional internal quality specifications from buyers that suppliers must comply with, for just-in-time delivery or ripening process. The average value for BRIX is 14%, and the dry matter is 16.5%, although there will be differences based on buyers, time to market, and variety.

In contrast, the OCED, with members from several continents, is yet to define mango quality with objective internal parameters like BRIX or dry matter. The 2020 OCED International Standards for Fruit and Vegetable updated protocols for mangoes. They suggest using fruit size, shape, and external color to judge maturity. However, they only mention that fruits must be mature enough to continue the ripening process. Since many member states already use dry matter and BRIX, adopting these objective parameters can smoothen international mango trade.

Processing Mango

Figure 2. “Processing of different products from mango,” Owino and Ambuko 2021. (Image credits: https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11111105)

Postharvest losses in developing countries like India, Rwanda, Benin, and Ghana can be anywhere between 30-80%. These losses occur during harvesting, packing, and distribution. Fresh mango can be processed even by small-scale growers to make primary processed products like pulp or secondary products like ice creams and beverages.

Fresh-cut mangos need minimal processing of cleaning, peeling, cutting, and treatments, followed by canning or drying.

The mango maturity and ripeness will differ based on the processing, and so will the quality parameters of BRIX and acidity to differentiate the products. For example,

making pulp requires ripe mangoes. The pulp has to have standardized BRIX of 14–18°and 4–6% acidity. After which it is pasteurized and sealed. From this pulp, many secondary products can be made, as shown in Figure 2:

● Mango juice that has 12-15% of °Brix and 0.4-0.5% acidity.

● Juice concentrate has to have 28-60% °Brix.

● Mango squash, a concentrated drink, has 25% juice, 45% °Brix, 1.2 to 1.5% acidity, and a preservative.

● Mango nectar is like squash except that it has no preservatives. It has 20–33% pulp, 15% °Brix, and 0.3% acidity (citric acid).

● Mango leather is made by drying pulp in sheets and contains 15–20% moisture content.

● Mango powder is made by drying the pulp with spray, vacuum, freeze, or drum dryers. The powder has only 3% moisture.

It is also possible to make dried products from mango slices. First, the fruits are washed, peeled, pitted, and sliced. Then they are treated with sugar and citric and ascorbic acid before being dried at 50-65 °C.

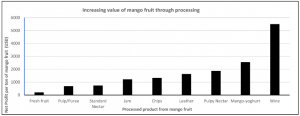

Though most mango is consumed fresh, processing the fruit reduces food losses and extends shelf life and income, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: “Net profits (USD) derived from processing 1 ton of mango fruit into various products, Owino and Ambuko 2021. (Image credits: https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11111105)

Making the Most of the Yield

Quality improvement in mangoes is necessary to meet market demands and reduce postharvest losses, over 50%, in some developing countries. A combination of approaches from simple local techniques to state-of-art technology like NIR spectroscopy can help mitigate these losses. NIR spectroscopy allows control and monitoring from the preharvest stages until the fruit reaches the retailer.

Sources

2022 fresh mango global market overview Today. Tridge. (n.d.). Retrieved September 30, 2022, from https://www.tridge.com/intelligences/mango

Abceditor. (2022, May 17). Mango crop report 2022 – Detailed analysis of Alphonso and totapuri mango crop by region. Retrieved September 30, 2022, from https://www.abcfruits.net/mango-crop-report-2022-alphonso-and-totapuri-varieties/

Abdalla, E.A., Osman, M. S., Elsiddig, M., et al. (2016). Using Local Materials in Traditional Storage of Mango (Mangifera indica L.) Fruits in Sudan. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333105888_Using_Local_Materials_in_Traditional_Storage_of_Mango_Mangifera_indica_L_Fruits_in_Sudan

Alphonso growers from Maharashtra to sue sellers of fake varieties. Retrieved from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/74234516.cms?Utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

APEDA. (2009, Feb). Pre harvest and post harvest operations for sea shipment of mango. Retrieved from

Chatper, H.S., Gai, G., Mattoo, A.K. and Modi, V.V. (1972). Some vii. Harvesting, storage and transport of mango – some problems pertaining to storage and ripening in mango fruit. Acta Hortic. 24, 243-250. DOI: 10.17660/actahortic.1972.24.49

FAO. (2018). Low cost, high impact solutions for improving the quality and shelf-life of mangoes in local markets. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/3/I8327EN/i8327en.pdf

Jannoyer, M., Urban, L., Léchaudel, M., Normand, F., Lauri, P.-E., Jaffuel, S., Lu, P., Joas, J. And Ducamp, M.-N. (2009). An integrated approach for mango production and quality management. Acta Hortic. 820, 239-244

DOI: 10.17660/actahortic.2009.820.26

Mango production by country 2022. (n.d.). Retrieved September 30, 2022, from https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/mango-production-by-country

Mango Crop Report. (2022, Sept 23). Retrieved from

Https://www.mango.org/wp-content/uploads/PDF/Mango_Crop_Forecast.pdf

Mango Handling and Ripening Protocol. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.mango.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Mango_Handling_and_Ripening_Protocol_Eng.pdf

Odey, S.O., Agba, O.A., & Ogar, E.A. (2007). Spoilage of freshly harvested mango fruits (Mangifera indica) stored using different storage methods. Global Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 6(2). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343323398_Spoilage_of_Freshly_Harvested_Mango_Fruits_Mangifera_indica_Stored_Using_Different_Storage_Methods

OECD. International Standards for Fruit and Vegetables. Retrieved from https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/agriculture-and-food/mangoes_f9210db0-en-fr

Owino, W. O., & Ambuko, J. L. (2021). Mango fruit processing: Options for small-scale processors in developing countries. Agriculture, 11(11), 1105. Https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11111105

Siddiqui, M. W., Ayala-Zavala, J. F., Thakur, P. K., et al. (2011). Improving mango fruit quality through sap-burn management. Conference: Global Conference on Augmenting Production and Utilization of Mango: Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229085882_Improving_mango_fruit_quality_through_sap-burn_management

The Dollar Business Bureau. (2017, July 10). Mango exports to be down this year as production drop by 70% in UP. Retrieved from https://www.thedollarbusiness.com/news/mango-exports-to-be-down-this-year-as-production-drop-by-70-in-up/50756

TIS. (n.d.). Mangoes. Retrieved from https://www.tis-gdv.de/tis_e/ware/obst/mango/mango-htm/#

Vantage Market Research. (2022, July 21). Global Processed Mango product market projected to hit USD 3237.7 million by 2028 growing at 6.7% CAGR – report by Vantage Market Research. Globenewswire News Room. Retrieved September 30, 2022, from https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2022/07/21/2483432/0/en/Global-Processed-Mango-Product-Market-Projected-to-Hit-USD-3237-7-Million-by-2028-Growing-at-6-7-CAGR-Report-by-Vantage-Market-Research.html

Wijeratnam, S. W., Gunasekera, N., Suneth Gunathilaka, S., et al. (2015). Improving quality of mango (Mangifera indica) var. Karthakolomban by postharvest application of new edible wax formulations. Conference: Biennial Research Symposium, Sri Lanka. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294483896_Improving_quality_of_mango_Mangifera_indica_var_Karthakolomban_by_postharvest_application_of_new_edible_wax_formulations

Related Products

Most Popular Articles

- Spectrophotometry in 2023

- The Importance of Food Quality Testing

- NIR Applications in Agriculture – Everything…

- The 5 Most Important Parameters in Produce Quality Control

- Melon Fruit: Quality, Production & Physiology

- Fruit Respiration Impact on Fruit Quality

- Guide to Fresh Fruit Quality Control

- Liquid Spectrophotometry & Food Industry Applications

- Ethylene (C2H4) – Ripening, Crops & Agriculture

- Active Packaging: What it is and why it’s important