February 16, 2026 at 5:05 pm | Updated February 16, 2026 at 5:05 pm | 10 min read

- During the postharvest stages, kiwifruit quality deteriorates due to chilling injury, loss of firmness, microbial spoilage, bruising, and off-flavor development.

- Low temperatures used to store and transport kiwifruit cause chilling injury, which is one of the reasons for loss of firmness and the formation of off flavors.

- Physiological processes such as respiration rate and ripening, as well as exogenous ethylene, also cause loss of firmness, physiological disorders, and off-flavors.

- Fungal pathogens are primarily responsible for the microbial spoilage of kiwifruit during the postharvest period.

Kiwifruit, known for its flavor and nutritional value, is a relatively new crop, having been traded on the international market for around three decades. The kiwifruit market is estimated at USD 8.03 billion in 2026 and is expected to grow at a 4.16% CAGR through 2031. Exports are expected to grow as demand increases and trade liberalization, including lower tariffs between certain regions, takes effect. However, kiwifruit suffers from several quality issues during the postharvest stages, which supply chains must address to make the best of the commodity. This article examines key quality issues in kiwifruit and their causes for stakeholders working to improve kiwifruit quality.

Kiwifruit Characteristics

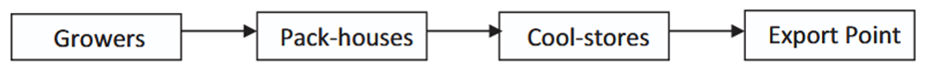

Figure 1: “Block diagram of kiwifruit supply chain,” Gautam et al. (2017). (Image credits: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2016.09.007)

Subscribe to the Felix instruments Weekly article series.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact

Kiwifruit come in a wide range of flesh and skin colors, but green-fleshed kiwifruit are the most popular, with red- and yellow-fleshed varieties gaining attention recently. It is cultivated and exported mainly from New Zealand, China, Greece, Italy, and France.

It is worth noting some of the physiological processes that influence kiwifruit quality in postharvest stages and determine conditions of storage:

- Ripening type: Kiwifruit is a climacteric fruit, in which an increase in respiratory rate at maturity triggers ethylene production, initiating ripening. Therefore, the fruits are transported and stored at 0°C for extended periods to reduce respiration and delay ripening.

- Harvest Maturity: As a climacteric fruit, kiwifruit can be harvested at full maturity, before ripening, to extend storage life. The maturity of fruits at harvest will influence their shelf life during the postharvest period and is used to determine their use, sorting, grading, and storage. To minimize maturity differences in fruits within an orchard, in addition to harvest maturity indices, New Zealand uses the concept of a maturity area, or a block of four hectares with similar maturity levels based on vine age, to avoid quality problems later.

After harvest, kiwifruits are packed in wooden bins and transported to packing houses. Here, they are tipped onto conveyors and shifted to tables for manual grading into Class I and II. Fruits below these grades are used locally as animal feed or processed into juices, puree, and jams. Graded fruits are individually weighed, labeled, and packed into boxes, then stored in cool rooms before long-distance transport or export: see Figure 1. Sending harvested fruits to nearby packers can reduce costs but increase the risk of contamination or storage at incorrect temperatures and humidity, which affects quality and subsequent revenues. Using RFID tags allows suppliers to identify the source country and orchard of spoiled fruit, enabling corrective measures.

The kiwifruit should be transferred to cold storage or a controlled atmosphere (CA) facility within a week of harvest. The ideal CA conditions for kiwifruit are oxygen (O2) concentrations of 2% and carbon dioxide (CO2) levels of 5%, with no ethylene.

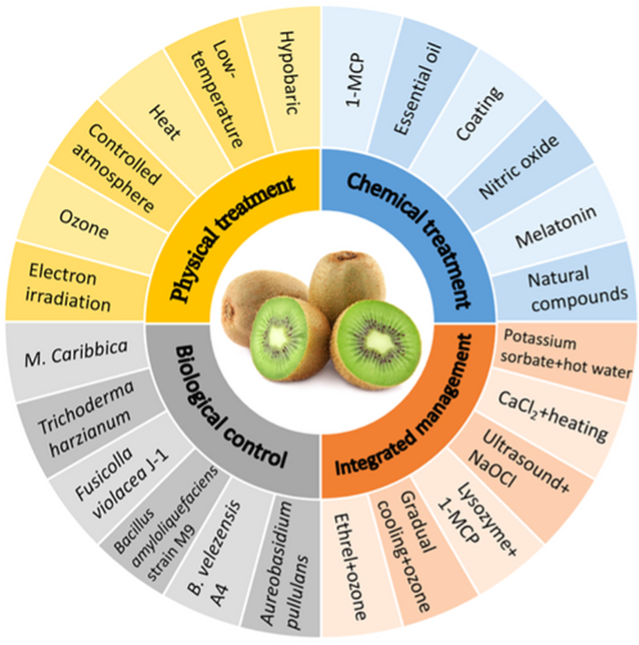

Chemical, physical, and biological strategies (See Figure 2) can enhance quality, but some quality problems persist at several points of the supply chain. These include chilling injury, microbial spoilage, oxidative damage, loss of firmness, off-flavor development, and bruising.

Figure 2: “A summary of different technologies for prolonging the postharvest life of kiwifruit,” Xia et al 2024. (Image credits: https://iadns.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/fft2.442)

Physiological Disorders: Chilling Injury

Keeping kiwifruit at low temperatures extends its storage life; however, it also causes problems. Chilling injury and softening are two issues associated with cold temperature-induced storage breakdown disorder in kiwifruit.

Chilling injury occurs when kiwifruits are stored at freezing temperatures for extended periods.

It results in surface pitting, brown and grainy tissue in the outer pericarp, and pathogen multiplication and spread when the fruits are transferred to ambient temperatures.

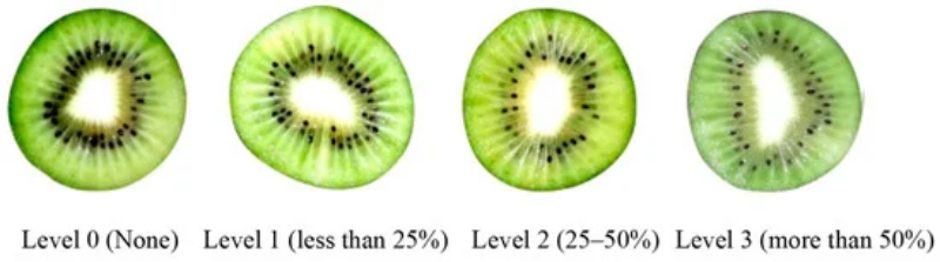

Translucency: Freezing damage starts as flesh translucency at the stem end and then progresses to the rest of the fruit, due to tissue deterioration; see Figure 3. Fruits start to look glassy or water-soaked. Pericarp translucency occurs during air and controlled-atmosphere cold storage at 0 °C, starting at the stylar end and spreading to the rest of the fruit. The symptoms begin after 12 weeks of storage and worsen with longer storage. The presence of ethylene worsens the condition.

Skin browning: When the tissue affected by translucency releases the phenols, which later undergo enzymatic oxidation, the tissue turns brown. When the damage is on the surface, the skin turns brown.

Figure 3: “Grading of translucency in kiwifruit pulp,” Xu et al. (2023). (Image credits: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/12/21/38929

Physiological disorders associated with chilling injury occur because low temperatures change the liquid-crystalline form of lipids in the cell membrane to a solid state, thereby making the membrane permeable and increasing ion leakage. The oxidation of membrane lipids and increased electrolyte leakage are the causes of skin browning. These are also the reasons for the flesh softening during cold storage.

According to Xia et al. (2024), the critical temperatures at which chilling injury occurs are specific to cultivars as listed below:

- For Ruiyu, it is −3.4°C

- Hayward it is −3.2°C

- Xuxiang can be cooled to −2.0

- Jinfu and Cuixiang it is −1.7°C,

- Hongyang tolerates only −1.4°C

Since kiwifruit is cold-sensitive and storage breakdown disorder is a critical quality issue for the species, alternatives to cold storage should be developed to enable long-term storage without its associated problems.

Miscellaneous Disorders

In addition to chilling injury, kiwifruit can experience a few other physiological disorders, as listed below.

- White core: White patches of core tissues are formed if kiwifruits are exposed to higher CO2 at 0 °C for more than three weeks.

- Hard-core: If kiwifruits are stored in controlled atmosphere facilities with high CO2 of 8% and ethylene, the core remains hard. It does not ripen with the rest of the fruit flesh.

- Internal breakdown: The condition begins as a discoloration caused by water soaking at the blossom end of the fruit and spreads to a large portion of the kiwifruit. A graininess also forms below the skin.

- Pericarp granulation: The condition occurs independently of translucency and starts at the stylar end of the fruit. It is most severe after the kiwifruit has been ripened at 20°C following prolonged storage.

Internal and external discoloration due to these disorders changes the fruit’s sensory quality.

Softening

To maintain kiwifruit quality, it is critical to minimize loss of firmness. Flesh softening in kiwifruits starts a few hours after harvest when stored in ambient air conditions. Softening occurs due to the conversion of starch to soluble sugars. Even when kiwifruit is stored at 0 °C, one-third to one-half of its firmness is lost.

Softening is considered to occur in phases in fruits. In the case of kiwifruit, scientists think it occurs in three to four phases, and the causal factor can differ across phases. For example, a three-phase mechanistic model by Gwampua et al. (2022) found that the initial rapid phase was caused by starch breakdown, the second slow phase by pectin collapse, and the final stage by chilling injury in the storage breakdown disorder.

In addition to low temperature, exposure to exogenous ethylene and harvest maturity can affect kiwifruit firmness. Each of the three possible factors is discussed below.

- Low temperature: Changes in cell membrane lipids that cause chilling injury also affect firmness. Also, chilling injury, by itself, is associated with changes in firmness and can lead to flesh softening.

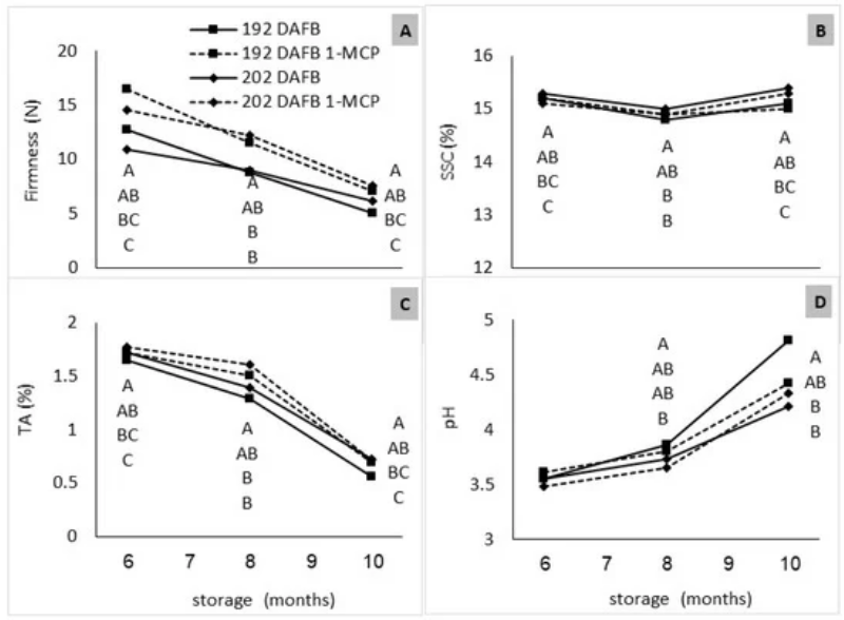

- Harvest maturity: Fruit maturity at harvest influences firmness during storage. Late-harvested kiwifruits retain firmness better than early-harvested fruits, see Figure 4. Fruits harvested at 5 pounds or higher in firmness will withstand vibration injury better.

- Ethylene: When kiwifruits are exposed to exogenous ethylene, it can induce unintentional ripening. Ethylene is autocatalytic; that is, it triggers more endogenous ethylene production in fruits exposed to the gas. It initiates physiological processes that convert starch into soluble sugars and soften the flesh during the ripening process. Exposure to exogenous ethylene can occur at any stage of the supply chain, including retailers, and can cause loss of fruit firmness due to overripeness.

Figure 4: “Effect of Hayward kiwifruit harvest time on changes in firmness (A), SSC (B), TA (C), and pH (D) during CA storage, with or without 1-MCP,” Goldberg et al. (2021). (Image credits: https://www.mdpi.com/2311-7524/7/10/358)

Microbial Spoilage

Kiwifruit postharvest quality can be affected by several pathogens that cause fruit decay. Fungi are the leading cause of spoilage in kiwifruit during the postharvest stages and can infect the fruit during handling, storage, and distribution. Bruised, physically damaged, and sunburned fruits are more susceptible to pathogens. The most common diseases affecting postharvest kiwis are listed below:

Gray mold rot: Botrytis cinerea is the most detrimental pathogen infecting kiwifruit and can reduce yield by up to 30%. It begins at the stem end and spreads uniformly. Affected parts initially appear darker, but as time goes on, the fruit can be covered by white to gray mycelium, and that can spread to cover neighboring fruits too. Wounded and soft fruits are more susceptible to fungi. Immature fruits are not affected by B. cinerea.

Soft rot: This disease, caused by Botryosphaeria dothidea, is among the most prominent affecting kiwifruit, leading to significant quality and economic losses.

Some of the other fungal pathogens affecting kiwifruits in the postharvest stages are Alternaria alternata, Diaporthe phaseolorum, and Penicillium expansum. Controlling the pathogens remains a challenge in the supply chain, since existing chemical fungicides must be replaced with natural alternatives to address consumer concerns about food safety and sustainability.

Off Flavors

The kiwifruit aroma depends on sugars, acids, and a mixture of over 80 volatile compounds. Kiwifruit can lose flavor and develop off-flavors during long-term storage. Off flavors are caused by physiological disorders like flesh browning and decay.

The volatile compounds responsible for off-flavors are those needed to develop fruit aroma in kiwifruit and begin to form in small amounts during ripening. However, several factors, such as prolonged storage, low temperatures, and exposure to high CO2 and low O2, increase the production and accumulation of these volatiles, leading to off-flavors.

Compounds responsible for off flavors, such as ethanol, acetaldehyde, and ethyl esters, are formed during sugar fermentation. Hence, regulating sugar fermentation can control the production of these volatiles. Some treatments, such as 1-Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP), control off-flavors by suppressing fruit respiration during storage.

Bruising

Bruising in kiwifruit has received less attention, but mechanical damage can degrade physicochemical quality during postharvest stages.

Collision frequency and collision position are both important, but they have different effects. Frequent collisions increase weight loss and rapidly reduce firmness, and the calyx/stem shoulder of kiwifruit is most sensitive to mechanical stress. More bruising can increase soluble sugar content (SSC), since stress releases ethylene that is responsible for ripening, during which SSC content rises. There is an associated reduction in titratable acidity (TA) due to ripening, especially when bruised at the calyx shoulder. The frequency of bruising will also reduce the effectiveness of nutraceuticals like vitamin C.

Bruising reduces sensory and nutritional quality and increases the risk of microbial contamination and spoilage, so collisions should be minimized wherever possible in the supply chain.

Monitoring Quality in the Kiwifruit Supply Chain

It is necessary to monitor kiwifruit quality during the entire supply chain, starting from before harvest. Harvest maturity indices can help pick fruits at the correct stage of maturity and sort and grade them. The physicochemical parameters of color, aroma, firmness, SSC, TA, and dry matter content should be monitored periodically to assess fruit quality at each stage of the supply chain. Moreover, portable and fixed gas analyzers can monitor the gas composition of CO2, O2, and ethylene in CA and ambient storerooms, enabling control of storing conditions to increase shelf life.

Felix Instruments Applied Food Science offers the portable F-751 Kiwifruit Quality Meter that estimates dry matter content, SSC, TA, and internal and external color simultaneously. It is easy to use throughout the supply chain and gives precise readings in real time. The company also has portable ethylene sensors customized for monitoring the air in storage and ripening rooms. It can also measure CO2 and O2 levels simultaneously. The F-910 AccuStore fixed device measures three gases, temperature, and humidity, and can control gas levels.

Contact us at Felix Instruments Applied Food Science for information on our instruments to improve your kiwifruit quality and revenue.

Sources

Crisosoto, C.H. and Kader, A. A. (1999, Nov, 10). Kiwifruit Postharvest Quality Maintenance Guidelines. Retrieved from https://ucanr.edu/sites/kac/files/123823.pdf

Gautam, R., Singh, A., Karthik, K., Pandey, S., Scrimgeour, F., & Tiwari, M. K. (2017). Traceability using RFID and its formulation for a kiwifruit supply chain. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 103, 46-58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2016.09.007

Goldberg, T., Agra, H., & Ben-Arie, R. (2021). Quality of ‘Hayward’ Kiwifruit in Prolonged Cold Storage as Affected by the Stage of Maturity at Harvest. Horticulturae, 7(10), 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7100358

Gwanpua, S. G., Zhao, M., Jabbar, A., Bronlund, J. E., & East, A. R. (2022). A model for firmness and low temperature-induced storage breakdown disorder of ‘Hayward’kiwifruit in supply chain. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 185, 111789.

He, K., Qiao, M., Liu, W., Sun, X., Fang, Y., & Su, Y. (2025). Effects of postharvest collision damage on qualities of kiwifruit during storage. Frontiers in Plant Science, 16, 1683638. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2025.1683638

Huan, C., Zhang, J., Jia, Y., Jiang, T. J., Shen, S. L., & Zheng, X. L. (2020). Effect of 1-methylcyclopropene treatment on quality, volatile production and ethanol metabolism in kiwifruit during storage at room temperature. Scientia Horticulturae, 265, 109266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109266

Liu, Y. F., Tong, X. Y., Xu, Z. H., Gao, Y. X., Cao, F., & Zhang, Y. H. (2026). Postharvest management of kiwifruit soft rot caused by Botryosphaeria dothidea using Magnolia officinalis essential oil: composition, efficacy, and mechanism. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 231, 113914.

Mordorintelligence. (2026, Jan 6). Kiwi Fruit Market Size & Share Analysis – Growth Trends and Forecast (2026 – 2031). Retrieved from https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/kiwi-fruit-market

Veeregowda, P. M., Jeffery, P. B., Johnston, J. W., & East, A. R. (2022). A survey of retail conditions in the kiwifruit supply chains of India and Singapore. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science, 50(2-3), 274-285.

Xia, Y., Wu, D. T., Ali, M., Liu, Y., Zhuang, Q. G., Wadood, S. A., … & Gan, R. Y. (2024). Innovative postharvest strategies for maintaining the quality of kiwifruit during storage: An updated review. Food Frontiers, 5(5), 1933-1950.

Xu, R., Chen, Q., Zhang, Y., Li, J., Zhou, J., Wang, Y., Chang, H., Meng, F., & Wang, B. (2023). Research on Flesh Texture and Quality Traits of Kiwifruit (cv. Xuxiang) with Fluctuating Temperatures during Cold Storage. Foods, 12(21), 3892. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12213892

Yang, S. Z., He, M., Li, D. M., Shi, J., Peng, L. T., & Liu, J. J. (2023). Antifungal activity of 40 plant essential oil components against Diaporthe fusicola from postharvest kiwifruits and their possible action mode. Industrial Crops and Products, 194, 116102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.116102

Related Products

Most Popular Articles

- Spectrophotometry in 2023

- The Importance of Food Quality Testing

- NIR Applications in Agriculture – Everything…

- The 5 Most Important Parameters in Produce Quality Control

- Melon Fruit: Quality, Production & Physiology

- Fruit Respiration Impact on Fruit Quality

- Guide to Fresh Fruit Quality Control

- Liquid Spectrophotometry & Food Industry Applications

- Ethylene (C2H4) – Ripening, Crops & Agriculture

- Active Packaging: What it is and why it’s important